Ultramarathoner:

‘a person who derives great personal satisfaction from experiences that include, but are not limited to, oxygen deprivation, dehydration, chafing, blistering, vomiting, cramping, toenail loss, heat stroke, and hypothermia; and preferably all at once.’

Eyeballing a world map over a few beers, and mulling over how to combine my genuine passion for running and travel I notice that Vietnam appears to be a long slender country, and suffering a severe attack of optimism I get the numbskull notion that it may be possible for this weekend warrior to run across it.

The fact I’m several years past a semi-century and have not been training somehow seems of little consequence. Instead, the idea seems more plausible with each beer making the journey down my throat. I mean why settle for dipping a toe in the water when you can do a cannonball off the dock!

Feeling very ‘ego-testicle’ and far too cocky for my own good I tell friends of my plan. This is the end of the beginning; I am now committed – or perhaps should be! The area chosen for my ambitious task is the province of Quang Tri in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. Starting at the Laos border at Lao Bao, my planned route will hopefully take me through the Annamite Mountains and along Route 9 through the infamous DMZ to Dong Ha on the coast; a distance of 84 Kilometers.

Quang Tri was one of the most heavily bombed parts of the planet during the ‘American War’ with an estimated four tons of weapons dropped per square meter; along with the earth being scorched with more than 700,000 gallons of deadly Agent Orange! The badly misnamed Demilitarized Zone split Vietnam into the communist north and the U.S. backed south, and was one of the war’s most gruesome battlegrounds with over 100,000 killed. Both sides defended their frontlines with everything they had, leaving the wastelands of the DMZ infested with an enormous cache of landmines and unexploded ordnance.

Since the war ended there has been over 4,000 civilians killed in Quang Tri province by leftover bombs or mines, and tragically in a typical week at least one child is still killed or maimed. The area is definitely not a place to stray from the road if you value your extremities. Oh well, I never relished being shackled to sanity!

Researching the route before leaving Canada I get some news I can use from the Canadian Consulate, indicating special permission from the Foreign Relations Department in Quang Tri Province is required. Getting information on the area is like grabbing fog, but after much correspondence a few documents are provided. With many questions still unanswered, and considerable trepidation, we are on our way.

After three weeks of travel in Vietnam we arrive in Hue and arrange for a driver and guide to help Christine who has volunteered to be my support staff during the long distance endeavor. Hue is known as the ‘City of Ghosts’ because of the Viet Cong slaughtering some 3,000 people suspected of sympathizing with the south. Despite almost being bombed into oblivion during the American War, the city somehow survived.

Driving a ridiculously rutted road, we proceed towards the Laos border to reconnoiter the route for tomorrow. When the car stops short of the border we ask why, and interpreter (Mr. Huy) and driver (Mr. Thanh) inform us Lao Bao is a smuggling area with a glut of corruption and they’re afraid of the police.

Suddenly a comical sight unfolds when a group of cigarette smugglers looking like the Michelin Tire Man appear. Waddling right past us in order to bypass border guards they futilely attempt to hide enormous quantities of cigarettes taped to bodies beneath baggy oversize coats. With their range of motion seriously impaired by the cargo they are a comical mess in motion and look as awkward as a T-Rex sipping a martini.

Returning to Khe Sanh, we look for a place to spend the night so I can begin my run at daybreak. Scouting out two government guesthouses we find both appalling, but in chatting with locals our interpreter comes up with an alternative plan. We follow him to a brand new building which turns out to be a bank, where the manager lives in one room and has two others for rent. Surprisingly, the room is cleaner than a nun’s browsing history and even has hot water and a western toilet! We’re even more astonished when a young girl brings fresh-cut roses and a pot of tea. We’re hoping our good fortune is a precursor of what’s to come.

December 18, 2000 is the day! We arise at 4:00 a.m. and fuel up on baguettes, jackfruit chips, and a bag of peanuts. Not exactly a breakfast of champions, but in this region finding suitable food is a real problem. The four of us set off for the Laos border in the pre-dawn hours as if in some kind of clandestine operation.

05:30 – The Laos border. My mind is occupied with how this significant challenge is about to unfold; hoping it ends heroically and not as a doomed endeavor. With the night in retreat we use the stealth of a jaguar to sneak a forbidden photo at mile zero. Then, with my body squirting adrenaline out of its glands from the exhilaration of pushing into the unknown, my date with destiny begins.

06:15 – Encounter women from the Bru hill tribe smoking from long-stemmed pipes stuck in mouths stained a reddish black. Strapped to their backs are baskets of bananas, and having never met a carbohydrate I didn’t like, I stop to buy a couple. With the women gaping at me and looking more confused than a chameleon in a box of Smarties, I’m quickly off again, feeling wondrously alive and alert to whatever waits around the next corner.

06:40 – Pass through Lang Vei where a bloody, brutal, and costly battle for the U.S. and its allies occurred when a North Vietnamese Army tank-led infantry task force overran the Special Forces Camp. Sitting on a slab of pink cement is a memorial of an old army tank (#268) which commemorates the victory.

07:30 – After a steady 20 km uphill battle of my own through a cold kiss of fog in the Annamite Mountains, I pass an old lady walking barefoot along the slippery road carrying one of the ‘black dogs’ considered to be a delicacy. In Vietnam dogs are better appreciated as a dinner rather than as a member of the family!

07:45 – Pass the infamous Khe Sanh combat base, and running is tough on a rain-slickened road shrouded in a red mud. The colour somehow seems appropriate given this was the scene of the longest and bloodiest battle of the Vietnam War. The lush jungle surrounds were also devastated by dumping a shitload of Agent Orange to deprive guerilla forces of cover.

08:00 – Starting the steep descent through the mountains my spirits are buoyed by melodious bird calls emanating from somewhere in the mist, but I feel the first sign of ache in my legs. Christine is smitten with her newly purchased pointy Vietnamese hat. It acts as a pitched straw roof over her head and helps to keep her dry with the water sliding down its sides and out past her shoulders. A functional bonnet indeed!

08:45 – Rounding a sharp bend I leap into a ditch to avoid obliteration by an enormous freight truck on the wrong side of the road attempting a suicide pass of a bus on a blind corner! Propelling past me, the metal monsters belch out thick black diesel fumes and resemble giant octopuses ejecting clouds of ink. It seems vehicles with four or more wheels fancy themselves the only legitimate highway users in these parts, and with people and animals at the bottom of the food chain I’m relieved to avoid becoming runner road kill!

09:20 – With another 51 km still to run I reach the famous Dakrong Bridge. Stopping to throw up and get a dry shirt I am scolded by Christine for not drinking enough water. I pensively recall a humorous pre-trip email received from a tourist information center regarding my inquiry about this run. Verbatim, the note said: ‘Dear Sir: You don’t wary about the wide of 84 km; can run across Vietnam by train, or by car.’ Obviously to them, traversing the country ‘by legs’ is a completely unfathomable concept!

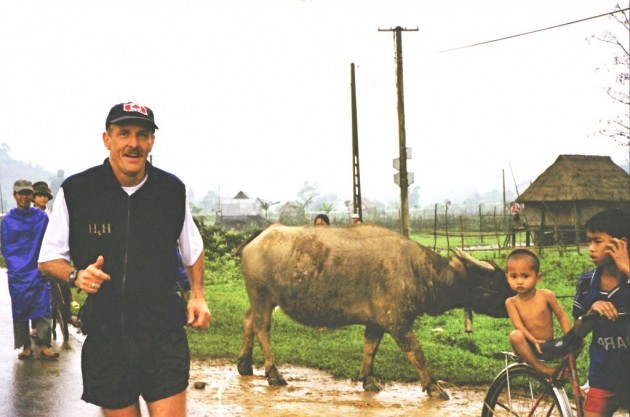

09:40 – Harpooned by a calf cramp, my ‘urge to surge’ has evaporated. Christine applies tiger balm to try and ease the issues with my tissues and I push on. In every village I run through people peer at me saucer- eyed, probably theorizing that this stranger with skin the color of cooked rice who runs with nobody chasing him doesn’t have both chopsticks in the same bowl. Very clever people these Vietnamese!

10:30 – The cold has always been my kryptonite, and after five hours it is starting to take its toll. With Mo and Mentum now divorced and my legs gone from niggling to nagging, I am acutely aware of the enormity of the task at hand, and the thought that I may be unable to finish is a gnawing horror within.

Passing a hill tribe burdened with bulky baskets of firewood makes me think about how hard they must work to survive, and how easy our lives are in comparison. I remind myself that surviving an ultra-marathon always comes down to your mental mettle and having the discipline to cope with pain. Some would say any idiot can run a marathon – it takes a special idiot to run an ultra-marathon!

10:45 – At the 42 km point I exclaim I’ve reached the halfway point and have only one more marathon to run. With the relationship between my mind and disobedient legs already in trouble, I realize in one of my more genius moments that ‘only‘, and ‘one more marathon‘, definitely do not belong in the same sentence!

11:00 – Route 9 meanders through picturesque countryside with stilted thatch-roofed villages scattered along the Cua Viet River. A woman standing outside a hut uses a wooden pestle as tall as herself to pound grain in a mortar created from a hollowed out log. Another passes by with one arm holding an infant on her hip and the other arm stick-thwaping the rump of a lethargic water buffalo.

11:20 – I run past a fellow with a mobile garden shop on the back of his bicycle and he follows me; tenaciously attempting to sell me a tree that he thinks I might need! Damn, I wonder if he pulled a groin muscle jumping to that conclusion! If brains were leather I seriously doubt this guy would have enough to saddle a mosquito! With small muscles tugging up the corner of my mouth I plod on.

12:00 – Cold and miserable, my lower extremities are passionately protesting and my confidence stuttering as gung ho exuberance collides head-on with a wall of reality. Stopping on the side of the road to massage a leg cramp, we attract a large audience of rag-tag children gawking wide-eyed at the strange sight before them. Cocooned in determination I force myself up and shuffle off at the speed of an arthritic three-toed sloth, followed like the Pied Piper with the boisterous bedraggled bunch in tow.

13:00 – My beleaguered body parts are in revolt, and experiencing intestinal unrest, I throw up a second time. After 7 ½ hours of running I had planned to be finished, but much to my chagrin still face many more merciless miles ahead. Christine is fretting over my enfeebled condition and wants me to stop, but this run is extremely important to me and I don’t plan to tap out under any circumstance. My lovely wife has always said ‘if you can look in one ear, and see light out of the other, you’re looking at an ultra-runner’!

13:20 – I pass the Rockpile; a 350-meter high rocky hill used by US Marines as an outpost. Coming to an area being dynamited I am detained by workers until the blasting and falling rocks have ceased. I’m hoping this break will provide a resurgence of energy, but it’s just misplaced optimism. With my mind and the misfiring neurons in my legs at war, the desperate struggle between a set purpose and an utterly exhausted frame continues.

14:00 – My body is now shivering and my dream starting to turn into a nightmare. With my distress reaching epidemic proportions it feels as if I’m trying to empty the ocean a teaspoon at a time. I guess the moral is if you’re going to try and run across a country in a day – DON’T! Yes I know, many draw wide admiration of my almost Socratic wisdom!

14:35 – Alone with my thoughts and my creaky legs betraying me, I stop for water before continuing on with the grace of an elderly tortoise with tendinitis. Deep in the muck of my misery, every step is demanding a decision; give in or fight on. I remind myself that to finish an ultra-marathon the ‘can’ of the heart must overcome the ‘can’t’ of all the other muscles.

15:30 – Ten hours into the run I reach a restricted area at Cam Lo where the car cannot stop. A rifle-toting military guy grabs at my arm, but since my passport and permits have gone ahead in the car, I’m afraid that if I stop I may not get going again. With fatigue temporarily forgotten and a sudden energy boost powering my pace, I shrug off his hand without stopping and point ahead yelling ‘Dong Ha – Dong Ha’!

He is shouting some Vietnamese mumbo-jumbo at me and I’m as nervous as a cucumber in a convent, dreading what may happen next! Afraid to look back I keep running, and at 52 years of age suddenly find religion. May the Lord have mercy on my soles! Fortunately my prayers are answered when nothing happens, and a few kilometers later bone-deep relief washes over me as my eyes find the car.

16:00 – With over 70 km already run and my toes rubbed raw I am ambushed by Hypothermia. I’ve stopped sweating and starting to wobble. My mind is telling me ‘you’re going to make it, you’re going to finish’, but my quivering quads are not experiencing the same confidence. The car is now stopping every kilometer to check on me as Christine’s composure has become unraveled by my condition.

Again being followed by a bunch of boisterous kids I stop to ease another cramp, and the kids somehow have a bicycle pile up. All of a sudden the youth in Asia seem keen on providing euthanasia! Appallingly, one of the little fuckers chucks a rock and hits me right in the ear with it, dropping me to my knees and leaving me stunned, with what sounds like a swarm of hornets invading my ear-hole.

I am pissed by the unmerited aggression, but out in the middle of nowhere and feeling woozy, all I can do is put away the pain and carry on. With ultra-marathons it’s all about dogged determination over distance, but the problem with such a deep reservoir of stubborn is you risk drowning in it!

17:00 – Despite approaching darkness and complete fatigue claiming everything south of my hair, I cling like a barnacle to my indomitable devotion to motion. Swallowing my misery I struggle on with my pace now slowed to the point I could be rear-ended by a sleepy snail. My mental mantra is ‘Please let me survive to the end. PUHL-ease let me finish’!

17:37 – Christine leaves the car to be by my side and finally her gaze falls upon the DONG HA sign! Gasping like a goldfish removed from its bowl, I stagger to the sign. That wonderful and gorgeous sign! After 84 kilometers and some 80,000 leg jolts of panting purgatory, this Sisyphean task has pretty much obliterated me, but I have remained unbreakable. I have made it. I have actually run across Vietnam!

We are told nobody has ever done this before, and if this is so I am truly honored to be the first. It just goes to show that with ordinary talent and a grit that won’t quit all things are possible. Christine takes the momentous photo and I collapse inert into the car. However, the day is far from done.

Christine, my rock throughout, suggests going to the hospital in Dong Ha, but apparently I talk her out of it and we begin the drive back towards Hue. From this point I am out of it and know nothing about what is actually happening, so I’ll use Christine’s account of the events that follow.

18:15 – Mark is now delirious and vomiting in the car. His breathing is fast and labored and he feels quite cool. Seriously troubled, I ask our guide to find a hospital in Quang Tri town, fearing we may not make it back to Hue without medical attention. In retrospect I’m kicking myself for not pulling him off the run, but this is a fleeting thought as I must focus on getting him through this ordeal.

Arriving at the decrepit looking Trieu Hai Region Hospital, Mark is lifted into an old wheelchair more lopsided than a Cuban election, and wheeled down a long hall through metal doors into intensive care. I am appalled at the disagreeably damp room with walls that appear to be growing a patina of mold. We get Mark up onto the bed and he is struggling, asking me not to let him drift off. My heart is breaking, but I must remain logical.

I put my intensive care nursing background to work, giving instructions to Mr. Huy to relay to the doctors and nurses. A tank of oxygen with a patina of rust is brought in and O2 provided. Next, I check the needles the doctors have brought out before intravenous fluids and electrolytes are hooked up. Blankets arrive, as does an electric heater that looks like it’s been around since people wrote with. Hot water bottles are applied over the IV tubing and chest area as Mark’s temperature has fallen dangerously low. Mark vomits up 2 or 3 liters of fluids over the bed and floor, and then to my horror, vomits up blood!

21:00 – My jaw is aching from chomping so hard on my worn-out gum and I realize I haven’t gone to the bathroom or eaten since breakfast. I find the bathroom which confirms the hospitals poor facilities, and when Mark has to pee they offer him a plastic IV bag with the top cut off! He asks for water & food, but when given a cracker, instantly vomits it back up. I’m most relieved there is no blood this time! A fourth bag of IV is given by the doctors who are doing a splendid job of everything and have my complete confidence.

21:30 – Mark is becoming alert, and realizing he is in a hospital, evil expletives begin spilling from his mouth on seeing the tubes and needle in his arm. Needles, especially used ones, are always a major concern when travelling abroad! Doctors want him to stay overnight but Mark has other plans. After a long discussion, doctors agree that if the impatient patient’s vital signs remain stable he can leave at 23:00.

Worried about payment to the hospital I ask our guide to have them prepare our bill, daunted by the fact we may not have enough money to cover the costs. However, it turns out I need not worry as the bill is only a miniscule 100,900 dong; the equivalent of about eleven dollars Canadian. Absolutely extraordinary!

The nurses and doctors are inordinately pleased that Mark has recovered. He is probably one of the very few Westerners they have ever had in their hospital. One doctor’s comment to me as translated by Mr. Huy is ‘We apologize for our poor facilities, but we did save your husband’s life.’ I start to cry.

We express our sincere thanks and appreciation to these wonderful folks who helped us in this most unlikely of places. Mark says he feels like he has been hit by a Mac truck, but to my surprise and delight he is walking out of the hospital after his distressingly close brush with mortality.

When leaving we try to give these kind people some extra money which they decline. Despite them steadfastly refusing, we leave it on the table, asking them to please purchase something for the hospital if they will not take it for themselves, because in Vietnam the people do so much with so little.

We owe an immense thanks to not only all the proficient hospital staff, but also to our interpreter and driver who kept us safe, found us the hospital, and stood by us through the whole incredible ordeal. With damp eyes Mark and I depart; extremely grateful and totally overcome with emotion.

Shortly after 1 a.m. we arrive back at our hotel in Hue, ending what has truly been a Sisyphean day. As we step out of the car, our astute guide Mr. Huy turns to Mark and respectfully offers a little pearl of wisdom: ‘Maybe when you recover, you try different sport; maybe like dancing!’

Perhaps the gentleman has a point!

Mark Colegrave/Christine Penney 2000